In 1975, at the end of the Vietnam War, a very unusual mercy mission was launched. Dubbed 'Operation Babylift', it was designed to take hundreds of Vietnamese babies and children away from the fighting to homes in the West.

Australian historian Ian W. Shaw has written about Operation Babylift, the women who drove it.

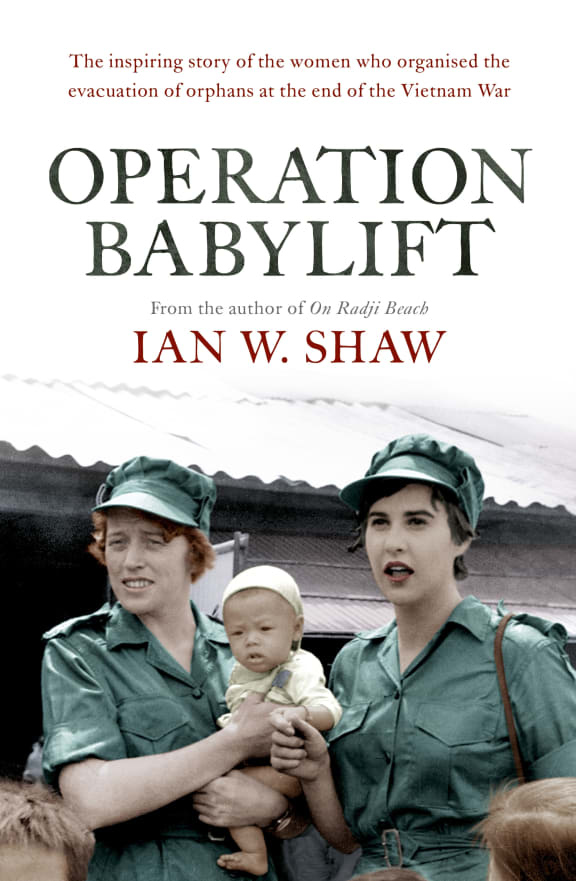

Rosemary Taylor and Margaret Mose were two former nuns from Adelaide who spent eight years in Vietnam during the war.

The pair developed a complex of nurseries to house war orphans and street children, and helped find adoptive families overseas for the children.

Taylor discovered that the mortality rate for children in orphanages in South Vietnam was up to 90 percent, says Shaw, and she realised that for most children, being sent to an orphanage in South Vietnam was a death sentence.

“She was very uncomfortable volunteering in that country, learning facts and figures like that, so she started her own adoption agency, but she called it a nursery rather than an orphanage.”

Her plan was to bring in sick children from orphanages in South Vietnam and nurse them back to health before finding adoptive parents for them outside of the region, he says.

“The story of ‘Operation Babylift’ is actually the story of Rosemary and the work she did,” says Shaw.

In a cruel twist of fate, the first flight laden with babies, children and their carers, crashed just after take-off when the cargo door blew off, killing all 138 on board, including Moses.

By the end of 1974, beginning of 1975, the North Vietnamese launched a series of attacks in the central highlands of Vietnam coinciding with increased raids in the South by the Vietcong. They were designed to test the will of not just the South Vietnamese government but the United States government, Shaw says.

He says it would have been through sheer strength of personality that Taylor was able to pull the operation off in such circumstances.

“She’s a woman of great determination and would not take no for an answer.”

Moses was the lightness to Taylor’s darkness, he says.

“She was very, very much a people person, she was very compassionate, very softly spoken and between them they were able to manipulate government officials to grant their children visas, to arrange transportation, all those things.”

Towards the end of the war, Australia believed South Vietnam was going to fall to the north and having pulled out in 1972, the country felt it owed the country, the US felt the same and so ‘Operation Babylift’ was hatched.

"The plan was to airlift 3000 orphans out of Saigon, fly them via the Philippines and Guam to California and land them there to much fanfare. For the Americans, it was something of a saving of face after the potential loss of South Vietnam."

In Australia the reformist Whitlam government, jumped on the bandwagon, Shaw says, and at the very last minute organised flights.

“This was a government that had resisted till the very last moment admitting South Vietnamese orphans into Australia for racist reasons I’d have to say, for political reasons, for a whole lot of things.”

It was the opposition and public opinion that caused a change of mind, Shaw says.

The flights themselves were rushed, and a traumatic event for the children. The US flight crashed, and the first Australian flight Shaw describes as a “monumental stuff up”. There weren’t enough carers and several fatalities, he says.

“Everything that could possibly go wrong, by and large did go wrong.”

By April 1975, some 4000 Vietnamese children were adopted outside of South Vietnam.

In the end, about 200 children were flown to Australia, although the exact number is unknown, because a number of South Vietnamese children were smuggled out as orphans but accompanied by their caregivers who didn’t want to remain in the country.

With the stress of only knowing Australia but being told they were different many of these children suffered mentally, Shaw says.

“When these children became adults and married and started to have children of their own, here in Australia it was quite common for them to want to know who they were, where they were from.

“They had no real concept of who they were as a person, they were always the other, they were always a bit different and people struggled to this day, doesn’t matter why if they’re categorised as the other.”