Dr Eimear Egan with boxes of fish ear bones collected in the 197os that she has been using to analyse past climate. Photo: Eimear Egan / NIWA

Subscribe to Our Changing World for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, RadioPublic or wherever you listen to your podcasts

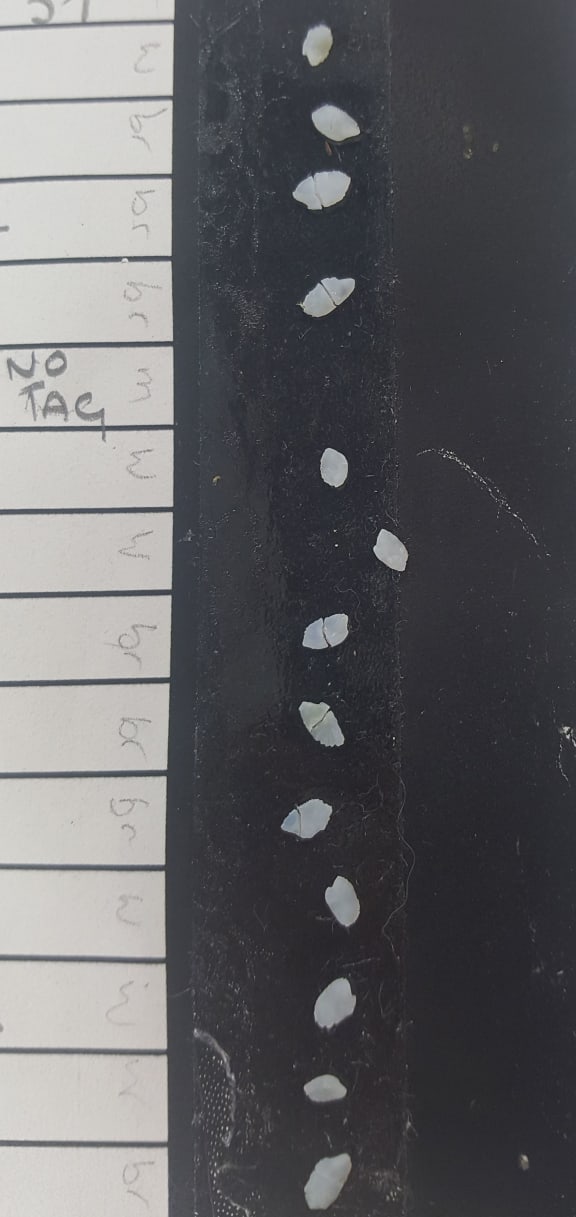

Ear bones from native freshwater fish are just 1-3 millimetres long. Their patterns vary between species. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Sitting in front of a microscope in her Hamilton laboratory, Eimear Egan is enthusing about some small dusty wooden boxes neatly filled with glass slides. She picks up some pieces of black paper, with rows of small white objects stuck to the page with aging sticky tape.

The pearly white objects, which resemble tiny shells, are ear bones, or otoliths, from eels and flounder. They were collected in the 1970s and carefully stored for future scientists like Eimear to investigate.

“These are longfin eels from Lake Hawea,” says Eimear.

The NIWA freshwater ecologist describes herself as an “otolith nerd”, and she has been gleaning insights into past climates from historic collections of eel and flounder ear bones collected from around New Zealand.

“All fish have ear bones,” she says, “and they come in all different shapes and sizes.”

Each species of fish has distinctive ear bones that are easily recognisable. Flounder ear bones, for example are highly serrated.

“They’re actually really beautiful and people make jewellery out of them,” says Eimear.

Otoliths are made from calcium carbonate, which also forms shells and egg shells and is used to treat osteoporosis and excess stomach acidity. Otoliths have a similar function to human ear bones, helping a fish with balance and with detecting vibrations in the water.

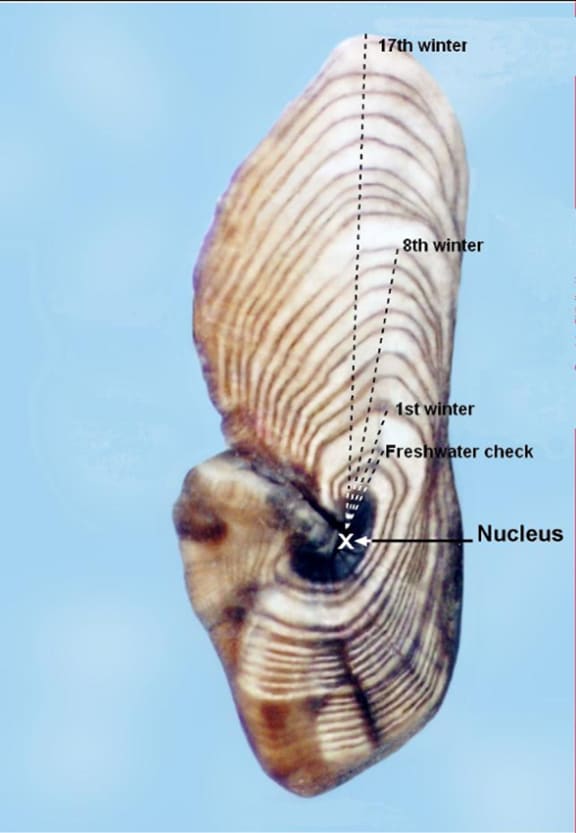

An otolith has a similar structure to a cross section of a tree trunk, with a central core surrounded by concentric rings.

“The dark centre in the eel ear bone represents its larval phase when it was at sea,” says Eimear.

“They breed in the western Pacific Ocean. We’re not 100 percent sure yet [exactly where].”

Later this year a NIWA team will be tagging longfin eels with satellite tags to try and find out exactly where New Zealand’s eels spawn.

An eel earbone showing clear annual growth rings. The central ring is year zero. Photo: Eimear Egan / NIWA

An ear bone from a 17-year-old eel. Photo: NIWA

As a fish grows it adds daily layers of calcium carbonate to its ear bones.

“It’s because of this daily deposition onto the otolith that we can extract information about a fish every day of its life,” says Eimear.

In winter, when the fish is growing more slowly, it lays down an annual ring, just like a tree ring. Eimear says that the annual rings have a different chemical make-up to the daily rings, and are very useful for determining the age of the fish, as each ring equals one year of life.

“There’s just so much information in the ear bones – they’re like diaries,” says Eimear. “They’re a treasure trove, really.”

“it’s amazing how something so small can tell us so much. It can tell us growth rates on a daily and annual and even seasonal basis. It can tell us their spawning dates and their age.”

The chemical composition of the rings can be analysed to provide details about what the fish was eating at different times and there are also check marks or distinct bands produced when the fish experienced stress.

“There are actually marks on the ear bone that represent feeding and when they transition from a larva into an adult,” she says.

The rings also record the varying chemical signatures of different water masses that the fish has lived in, while subtle variations in the shape of the otoliths can reveal whether there are subpopulations of a species.