Are standards of English declining, or is the language simply evolving? Some words like decimate and enormity are still dividing people.

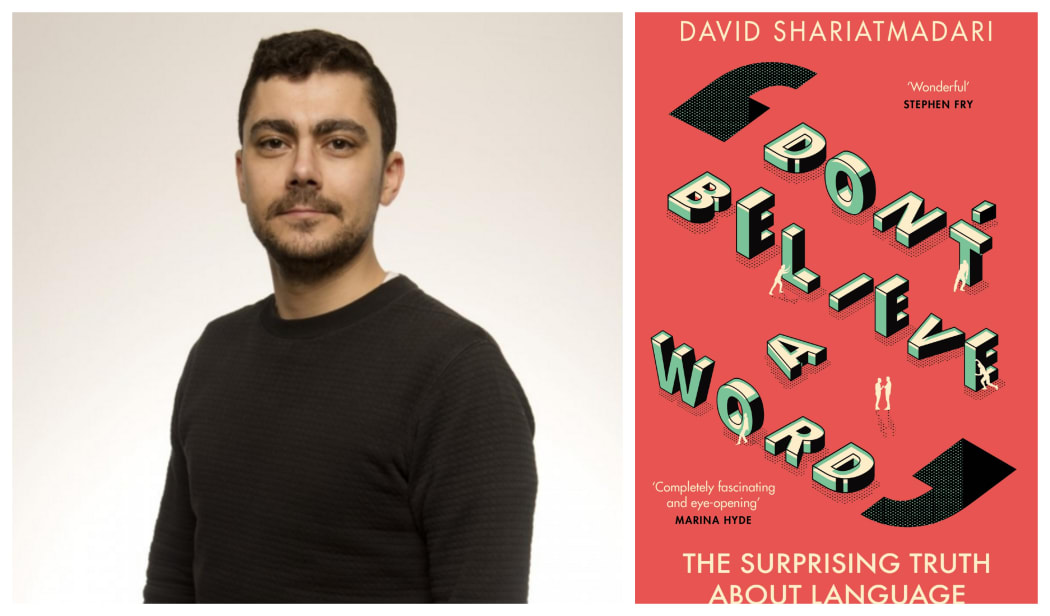

Editor, writer and linguist David Shariatmadari has a deep love of words, and an ongoing interest in how they emerge, change, and impact the way we think.

His new book Don't Believe A Word explores, then explodes, nine commonly-held myths about language.

David Shariatmadari / Cover of "Don't Believe a Word" Photo: supplied

Shariatmadari tells Kim Hill his fascination with language goes back to his childhood when his Iranian father would speak to friends in Tehran and Shiraz on the telephone.

“We’d hear him speaking this funny language, and he didn’t speak it to us and we didn’t learn it. By the time I got to university I thought I really had to find out what it was like to speak another language.”

He changed courses to Arabic and Persian and says learning a new language overturned his assumptions of what language is. Arabic he found particularly difficult.

“It’s kind of mind-boggling to someone who speaks an Indo-European language like English, that this completely different kind of structure exists. That really did open my eyes. I didn’t carry on learning Arabic for very long because it’s very hard, but I carried on learning Persian, the language of my father.”

Shariatmadari tackles a number of myths in the book, including the claim that language is going to the dogs. One example that’s often cited by grammar enthusiasts is the way the word 'decimate' is used incorrectly.

“This goes to the heart of an idea of language which is based around words having definitions which can’t change. Somewhere there’s a kind of guardian of words sitting there saying, this is what the word means and it doesn’t mean anything else. That’s actually a misconception about how dictionaries work.”

He says the word decimate originally came from decimation which was a form of tax. It was later used by Plutarch to mean the killing of one in ten men. Within 10 or 15 years of that, it was recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary as meaning to lay waste or to devastate.

“It’s been used like that ever since. So, the idea that the real meaning is that translation of Plutarch – to kill one in ten – is a bit wide of the mark.”

Research recently showed that the vast majority of the use of the word is to mean to lay waste and the only instances of people using it the way Plutarch did were people issuing corrections or complaints.

“The people who complain are providing the only instance of that use in the language, which is kind of remarkable, I think, given that they believe that is the correct use.”

Another word that gets some people angry is ‘enormity’, a word which Shariatmadari says has two co-existing meanings.

“One is hugeness, and the other is a very bad thing. I wouldn’t say that word really means a very bad thing rather than something very huge, because both of those meanings are used and language is created in its use, otherwise words would remain fixed for ever and we know that that is absolutely not the case.

“No one ever uses the word ‘nice’ to mean ‘sharp’ which is what it used to mean in the mists of time. Everyone has to admit that words do change. Sometimes it can be grating to see them change in real time, but that’s how language works.”