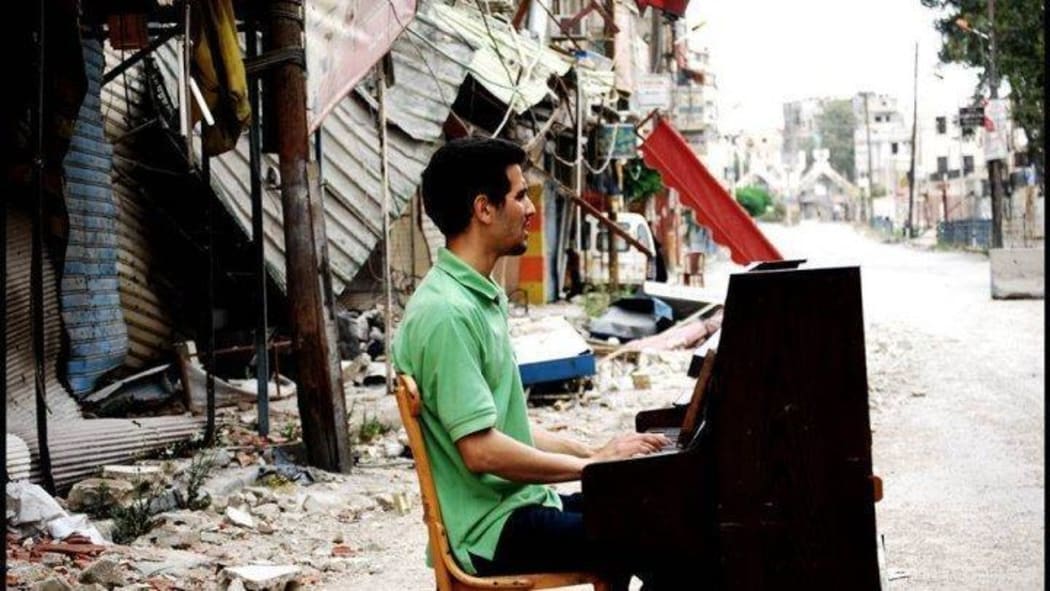

Ayham al-Ahmad became famous after playing his piano in the rubble of Syria's Yarmouk, a Palestinian refugee camp on the outskirts of Damascus.

His story of trying to bring a bit of joy against the backdrop of a war zone has gone viral. He told Jim Mora why he put himself in such danger and how life has changed after videos of him were put on YouTube. He has also written a book, The Pianist of Yarmouk.

Aeham Ahmad Photo: public domain

The crowded suburb of Yarmouk was poor, even before the war broke out, and al-Ahmad’s family was also not financially stable, his father had lost his eyesight through botched medical procedures. But al-Ahmad’s father became a sought-after piano turner.

His son began piano at the age four and grew into a talented player who sang about the horrors he saw to the people of Syria, and that was later captured and spread online for the rest of the world.

But al-Ahmad says it wasn’t easy to get a piano into Yarmouk after the war broke out and the community questioned his father over its importance considering the circumstances.

“Every time he’s fighting all the community to have a piano in Yarmouk camp and nobody understands why.

“My uncle, [he helped] carry the piano and every time he was telling him ‘oh why?! It’s so heavy. Ahmad, [it] will not enter the door’, and they take off the door, put the piano in and put the door on again because it was bigger than the door, he collected a lot of money from his relatives … he spent a lot of money for this piano.”

In 2012, the war hit Yarmouk hard with barricades going up and artillery shells exploding in the streets that people used to hustle and bustle in. The siege was brutal for the community, al-Ahmad says.

“We don’t have food, we are not allowed to head out from Yarmouk, we are not really allowed to have clean water, no medical equipment. We were slowly starving from hunger, 160 people dying from hunger and the number of rising of people being killed by bomb.”

He says it was made all the more difficult for the refugee community, who were mainly Palestinian refugees that were welcomed by the government, because they were not on either side of the battle and didn’t want to leave either.

“The Palestinian people, everybody in Yarmouk, they were saying we should stay and try not go with the revolution and not going with the government.

“We are not part of the fight, but we are inside the fight and this is happened in … a lot of cities.”

Al-Ahmad could have completely lost his ability to play the piano, or worse, when one day while he was striving to feed the hungry Yarmouk residents, a grenade exploded beside him.

“I made falafel in the streets with the beans, because we don’t have the real [ingredients] to make falafel but I tried to feed the people with something … 200 people were in the line, a lot of children, a lot of young people.”

Then a grenade exploded right beside the queue of people, he says, and he ended up injuring his fingers by 70 percent and his eyes.

“I began to think ‘the piano’s finished, I will not play piano anymore, and I began to think about, maybe I can make it with two, three fingers … but the situation was not only thinking about the piano … I won’t be able to complete the siege with three fingers, I can’t feed my family with falafel anymore.

“I began to think about the people in the line, I was injured with two fingers cut, but a lot of people were dying. You begin to feel guilty and think because they were in my line, and I feel all these things coming into one and you think ‘it’s finished’.”

His fingers were miraculously saved by the skills of a carpenter and he retaught himself to play the piano for his community.

“The people, the children, the same community that I made falafel for in the streets. I can reach the community directly and imagine when I give you … beautiful classical music after sitting in hunger for 12 days, you will not really hear it, you will think about your stomach that was the reaction of the people but the children they were happy.

“It’s something to keep you positive and to keep you thinking about solution. Without my music, I would not be here, talking with you on the phone or writing this book. All these horrible things around me, the music can make the light in the end of this darkness.”

In the background of his videos, gunshots can be heard, but he says the violence didn’t stop him from continuing. With his music flowing down the streets, the neighbourhood began to rally around the pianist and even gave him poems to recite alongside it.

It included a 12-year-old girl called Zainab, whose father had died and grandmother managed to escape. She wanted to film with al-Ahmad to show her grandmother.

“It was a crazy day, they told me to come and play and I didn’t have really the feeling to play in the street that day because everything [was] collapsed, and the war and the hunger was getting more and more strong.

“[The Yarmouk community] come and shout we need to play music.

“It was near her grandmother’s place, and she decided to go to this place … I decided to take another corner of the place, and she said ‘no, no, we need to make a video for my grandmother’ … my corner was safer but her corner was more dangerous, but it was the corner of her grandmother’s [house].

“We had the shooting and I see the girl near me, she was near the piano, dying and the blood, it’s crazy and every time I think about what’s happened and why it happened, I think why I didn’t stop it and say ‘no, it’s very dangerous today’, but it was dangerous everyday.”

The dangers didn’t cease any sooner, after that the control over the zone changed from one group to another, until it eventually landed in ISIS’ hands. Al-Ahmad says they burnt his piano while he was attempting to get across to another town to play his music.

Eventually, he ended up playing on the rooftops, where it was safer. But at the same time, it didn’t have the same power that it did before, he says.

“This music was not for the videos, not for YouTube … it was for the community and suddenly I played only for the sky and no birds also anyway, for the smoke around me and empty places – the whole thing collapsed after Zainab.”

While his music could not stop the war, it helped to stop the war sowing in his mind, he says.

“In Syria, my music gave me aim, it gave me something to work for, it gave me light in the end of the darkness and stop the war in my mind. War about ‘how I should carry water? How I should find food? How I can be free? How I can complete my music?’ It makes me busy with something positive.

“Everyday when I get my piano, I say, this is the last day. We die every day, maybe not by bombs, but all this horror … we think this is the last day. Again, I say we because all the community in Yarmouk was suffering the same way.”

When he finally managed to escape the zone and went to Europe, he never forgot his community. Al-Ahmad has been holding benefit concerts in Germany to help his community back home, and so far has also helped fund a hospital near Idlib.

The pain and memories still linger on his mind like it was just yesterday despite being out of there for three years, he says.

“When I remember all that happened and when I speak with you or write everything down in the book. It keeps me … remembering everything and this really hurts, because it will not help anybody, [it] only will tell the story what thousands people and million people tell, and this will not stop Erdogan, or Putin, or Trump to bomb people.”

Unfortunately, he doesn’t think he’ll continue to play the piano for much longer, but still takes great pride in being ‘The Pianist of Yarmouk’.

“It gives me great pleasure to not be the pianist during the bombing, this is what they call the concert in Germany sometimes, ‘the pianist between the bombing’, it gives me great pleasure to be the pianist of Yarmouk, for Yarmouk to not be forgotten.

“It’s not important [to have] my name, my family’s name, Yarmouk is important. This community that was living there is important.”