Professor Christopher Breward is a man who likes a good suit. He has one designed by Alexander McQueen which was crafted for him by Savile Row tailors.

The suit has been in and out of fashion for more than 400 years and Breward covers it all in his book The Suit: Form Function & Style.

Mr Breward is Director of Collection and Research at National Galleries of Scotland and says McQueen made very few suits and he treasures his.

He took the suit in lieu of a fee for curating a British Council exhibition.

"We needed a bespoke suit by the great British designer Alexander McQueen, sadly no longer with us, but who had trained in tailoring and then went on to produce these incredibly imaginative pieces that inspired a lot of people.

“He did a line of suits for a tailor in Savile Row. And we wanted one for the exhibition and a bespoke suit has to be made around a living body of course so I said to the British Council, well don't pay me, pay me in kind, and I can be the body around which that suit is made.”

The suit is a “glorious thing,” Breward says.

“….in pale blue Prince of Wales check with a white silk lining and when you put it on your body, you expect a Saville Row suit to feel somehow rigid, but it feels like water, it just follows, it's like a second skin quite literally.”

Breward defines the suit as a “three-part suit of clothing that comes together to produce a complete costume or uniform.”

There are competing theories as to the suit’s origins, he says.

“It's been with us for over 500 years, longer if you contest and argue about its origins.”

There are two theories main theories, he says.

“There's the theory that it gets introduced at the end of the 17th century in the courts almost simultaneously of Louis XIV in Versailles and Charles II in London, as part of the kind of modernisation of aristocracy and court society.”

Both monarchs wanted to control their courtiers by introducing a kind of uniform, he says.

“Which stopped all that stuff you got with the Renaissance courtier where they were showing their own power through wearing different spectacular costumes.

“But Louis XIV and Charles II wanted to be the spectacular ones, and they wanted their senior aristocrats to fall into line”.

Charles issues a decree that male courtiers should wear a three-piece outfit.

“A waistcoat, a jacket over the top and britches over white linen, a simple plain, costume embellished a little with ribbons and some embroidery but essentially a costume or a uniform.”

Another theory is that the suit emerged from the East.

"In Mughal culture in India through Islamic dress codes. If you think of the pyjama for example, which has its origins in northern Indian dress from the Mughal courts of the 16th century, then you can see exactly the same sort of cut.

“And this idea of the suit being all in the same fabric, but much closer in many ways to the lounge suit or the business suit that we understand today.”

Breward says he leans towards the latter theory.

“I'm quite interested in the way that that colonisation and Empire from Europe in the early period brings other traditions through into European cultures.”

The suit took another turn in the 19th century as a new breed of capitalists, with no royal associations emerged, he says.

“The great capitalists of the 19th century they almost reject ostentatious costume. And they choose to adopt these very well-cut, very well-made suits of distinction to show that they haven't come from a court society, that they are in control of their own wealth and their own identity.”

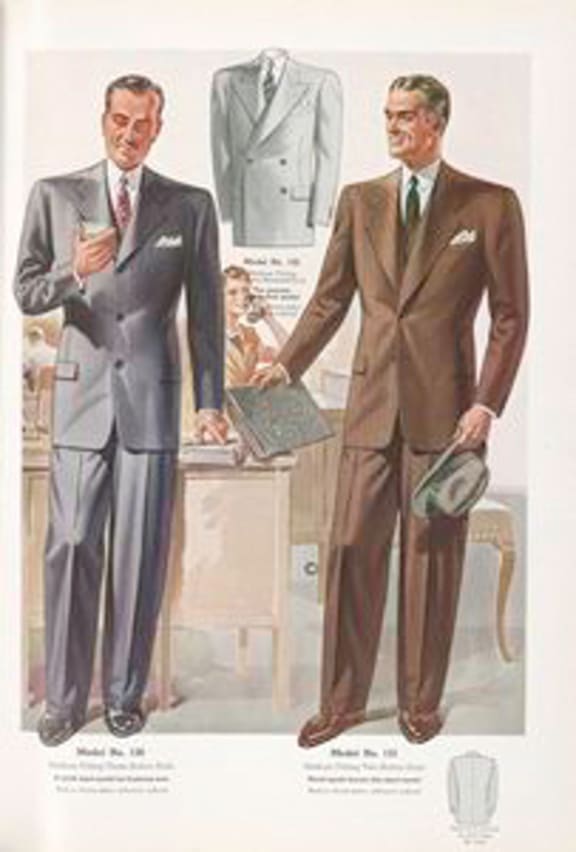

Photo: Supplied

The suit has been on the wane in recent times, he says. Although he detects a “little resurgence”.

"I was getting quite depressed with it because I'm interested in suits. I don’t wear them very much to tell you the truth, only on formal occasions and I kept reading in fashion journalism – the suit is out, sportswear is in. But this season, if you read the menswear journalists and you look at the menswear, catwalks, there is a return to tailoring in the suit again.

“But I think the suit has been very unpopular recently in popular discourse, because it might be associated with the rise of populism and the big personality, politicians who shall be unnamed, who wear the big suits, the big ties, the big man, that the suit has somehow become associated with those sorts of values.”

But the suit hasn’t always been associated with wealth and power.

“Some good examples of that would be, for example, in the music scene, the most famous example would be the Zoot suit in the 1940s.

"If you think of Cab Calloway, if you think of jazz in the 1940s, if you think of that big, bright suit, using lots and lots of fabric, almost disguising the body, huge pleated trousers, big bottoms with turn-ups, massive lapels, worn with jazzy ties, that became sort of very popular amongst immigrant communities in America in the 1940s, particularly Mexican and black American groups, who were wearing it as a symbol of their possession of space and culture in a society that was not necessarily friendly to immigrants.”

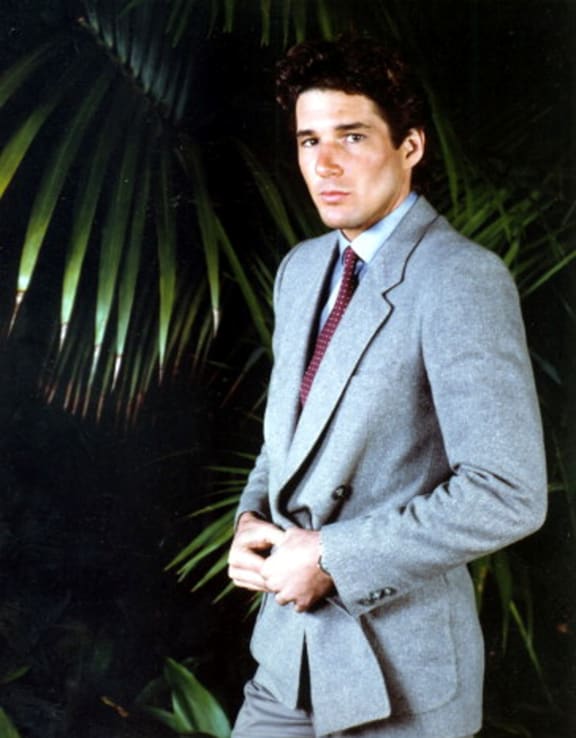

Photo: / CC2

During World War II the Zoot suit even provoked riots, he says.

“This ostentatious show of flash and colour and verve caused what were called Zoot suit riots in the streets of Los Angeles and other American cities, when young Mexican or black American men wearing the Zoot suits were attacked by GIs for somehow being unpatriotic.”

Women started to wear suits in the 19th century, he says, often in quite subversive ways.

“On the musical stage performers in Britain like Vesta Tilley, very famous, had a huge following, dressed up as fashionable young men around town, and sang these famous musical hall songs lampooning young men's stupidity in following fashionable taste, but became fashion leaders in their own right.”

In the 20th century some women also took to the suit as a badge of their sexuality, he says.

“We've got that great literary movement of writers who are dressing as men in the 1920s as part of an expression of a new lesbian identity that is offering new understandings of gender, I think, so Radclyffe Hall and that sort of moment in history is important or Romaine Brooks or women artists in particular.”