Martine Abel-Williamson is a powerhouse when it comes to creating positive changes to improve the lives of blind citizens.

“I’ve been living in New Zealand for 23 years this year,” she says with a smile.

When Martine lists everything she is involved in, like being the treasurer of the World Blind Union, vice president of Blind Citizens New Zealand, chair of Auckland Disability Law and on two ACC boards, she jokes that it sounds like she doesn’t have a life, but she does.

“Yes. I don’t feel like it every day, but you know what? I think advocacy is not a quick win in life ... Besides, there is far too much work to do."

Martine Abel-Williamson relaxing at home. Photo: RNZ Kate Orgias

Subscribe to Voices for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher and Radio Public or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

Martine is currently on the consumer advisory group and network for the Health Quality Safety Commission and she also helped develop New Zealand’s world-leading policy on the safe design of shared spaces for pedestrians and cars.

“People who do things in the community make a difference.”

In 2018, she received the Queen’s Service Medal for services to people with disabilities, and that same year took out the Attitude ACC Supreme Award for a lifetime of devotion to the support and advocacy of the blind community.

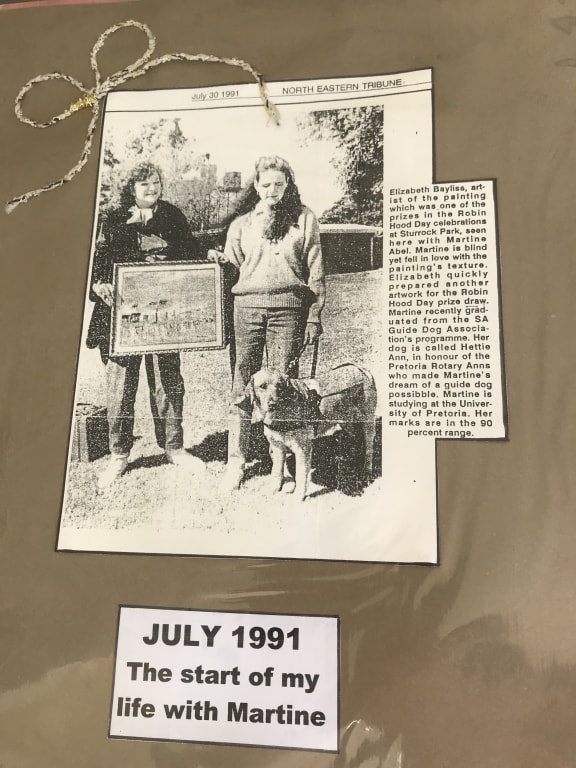

Martine learned early on in life not to sit on the sidelines. She was born blind in Namibia in the 1970s to a solo mother who already had a daughter from a previous marriage.

Her mother’s Dutch Reformed heritage created guilt for having a child out of wedlock and had her mum believing that having a blind baby was some form of punishment.

But in the end, she was an excellent parent, Martine says, always encouraging her daughter to develop her own personal skills that would help her make her own way in the world.

Martine learned later that this was at odds with the parents of her school peers.

“When I got to school there were some children there that could hardly walk because their parents would carry them everywhere… some were not even potty trained.”

Martine’s only option for an education was a boarding school for blind white children in neighbouring South Africa during the apartheid era.

“I didn’t realise for ages that I was in a school for white blind children, and that a neighbouring school was for Indian blind children, another for coloured blind children, and further afield was a school for black blind children.”

“I didn’t even pick up on that so for me it was more of a reflection afterwards.”

Since moving to New Zealand from South Africa, Martine has returned back a few times to visit. She says that while there is still a long way to go following the demise of the apartheid era in 1994, she has noticed positive improvements.

Martine came to Aotearoa with her sister, brother-in-law and mum in 1996.

“Making that decision meant spending the only cash we had, and it was like a done deal, you know. You can’t just say ‘oh, I’ve made a mistake, it’s too cold here I’m gonna go back’“ she laughs.

“You’re committed, and it was really stressful because my residency didn’t come through.”

Martine's New Zealand residency visa came through just before the date she had to leave the country.

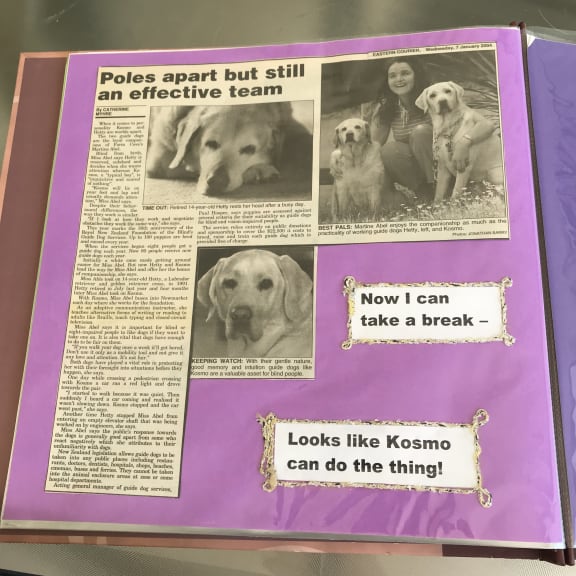

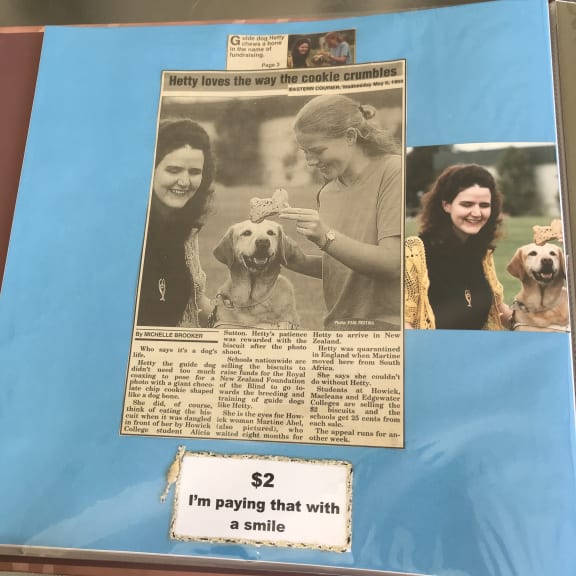

Then she had to wait another two months before her guide dog completed quarantine processes.

"At that stage, if you wanted to take your pet [to New Zealand], it had to go to either Hawaii, the UK or Canada for seven months quarantine before coming here."

It was two more years before Martine secured work and started to settle in here.

“It was a very stressful time.”

Two decades later, Martine now has a full calendar diary, is married to a New Zealander named Gary, and in September plans to travel to Canada for a conference about how airlines can better help blind people with their travel needs.

She says her view of Auckland has also evolved over time.

“I remember one of the first letters I wrote back to a friend ... I was here for two weeks and I said, ‘It’s raining and it’s raining and I’m sitting on 42 dormant volcanoes’ [Laughs]. So yeah, your perspective changes.”

“I think there’s a great lot of goodwill here and it’s extraordinarily culturally diverse. It’s quite an ideal spot to live in, really."

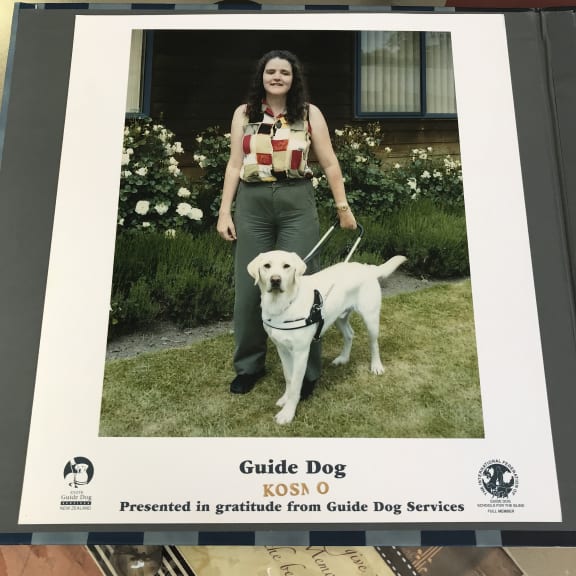

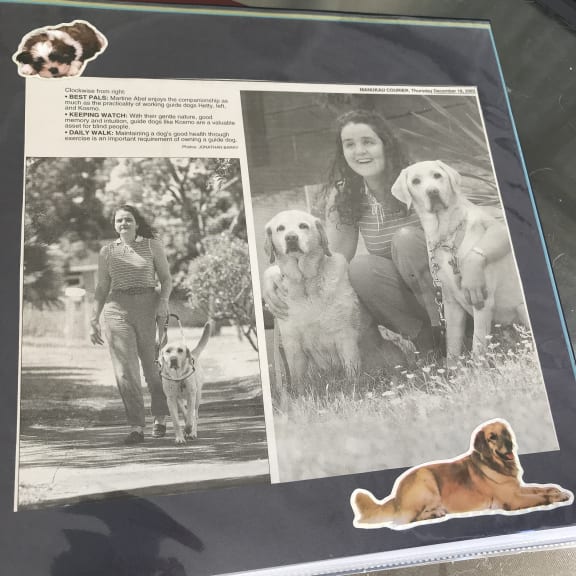

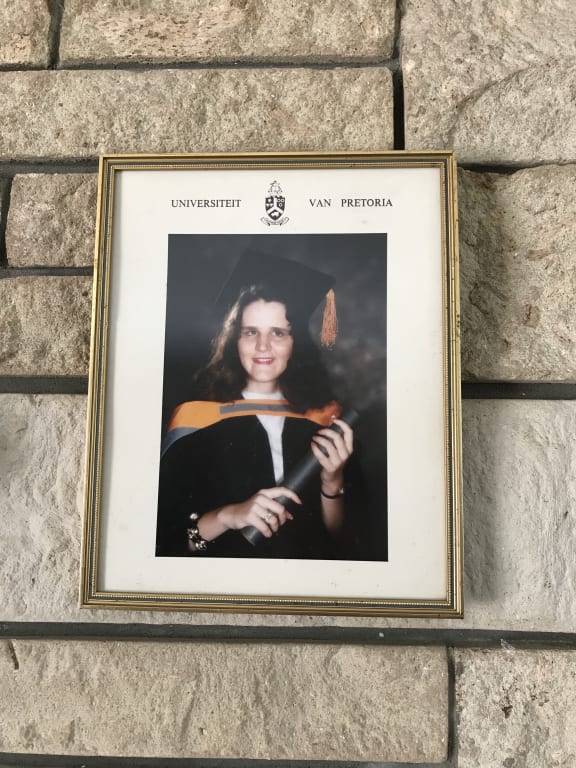

Photo: Supplied