Toa Fraser’s real-life hostage thriller 6 Days is a reminder of a more innocent age of terrorism, says Dan Slevin.

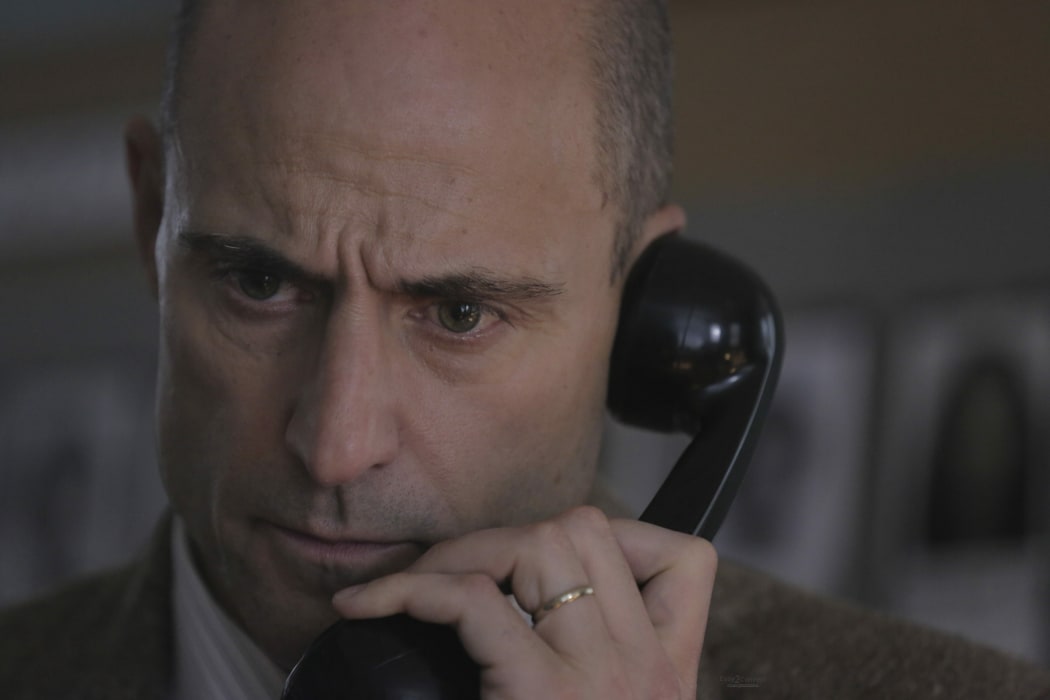

Mark Strong as negotiator Max Vernon. Photo: Transmission

I arrived in New Zealand in July 1986. Fancifully, I described myself as a refugee from Thatcher’s Britain, based on the fact that I was coming to a country with a Labour government. Nobody had mentioned Roger Douglas to me until it was too late.

The shadow of Mrs Thatch looms over Toa Fraser’s new film 6 Days (not Six Days, oh no), a tense and illuminating action drama about the 1980 Princes Gate siege, during which 25 hostages were held captive in Iran’s London embassy while diplomatic, judicial and military solutions were investigated.

Ultimately, the decision to send in the SAS (Special Air Service) to storm the building – in daylight and without a smokescreen – was the statement of strength that she needed to define her leadership.

She used that reputation to forge the Iron Lady persona that carried her through the Falklands, Miners and countless other conflicts, which in turn determined three decades of neo-liberal political hegemony. History, eh? One damn thing after another.

Abbie Cornish as the redoubtable Kate Adie, reporting live from the scene. Photo: Transmission

Fraser’s film is interested in historical context but only to tell us that terrorism has changed in that last 37 years.

In those days, terrorism was an opening gambit, a negotiating technique. Aeroplanes were hijacked or hostages were taken and then channels would be opened that might see political prisoners released or territories liberated.

Hans Gruber in Die Hard demands the release of pseudo-comrades in order to cover for his elaborate robbery. But things have changed – now terrorists are more likely to be suicide-seekers. In the 21st century, negotiation doesn’t come into it. Media coverage is more important.

Which is one of the stories that 6 Days tells. The negotiators – in the form of Mark Strong’s Max Vernon and Matthew Sunderland’s nauseous Tom Lovett – are racing against time to get a peaceful solution. They know the SAS are waiting in the wings and that the politics of the situation could easily get away from them.

The SAS are like Chekhov’s Gun – on the very first day they are masked, armed and ready to go in, only to be thwarted at the last minute by the release of an unwell hostage. Chekhov’s Gun is the theory that if a gun appears on stage in Act 1 it has to be fired by the end of the play. And, sure enough, the SAS eventually get the call.

Jamie Bell – once a ballet dancing schoolboy in the anti-Thatcher Billy Elliot – now takes orders from in 6 Days. Photo: Transmission

All of this is told in admirably accurate fashion – much care has been taken to honour every witness account – many of which have not been made public before.

The interior scenes were shot in Auckland, which explains why the two Fijian members of the SAS team look Māori and why some of the regional accents are a bit wobbly. Head of the assault team, Jamie Bell’s accent is mostly impenetrable but that’s probably more accurate than not.

The brilliance of this film is the revelation of what went on behind closed doors – in cabinet rooms and barracks, as well as the embassy itself.

As a young person, I watched the SAS do their thing (like 26 million other viewers) but all we knew was what journalist Kate Adie told us from her vantage point on the perimeter. (Abbie Cornish is going to be criticised for her BBC impersonation until people see how slowly we used to be talked to in those days.)

Based on – and honouring – first-person testimonies of those present, 6 Days delivers viewers the passion and adrenaline of a mission: impossible.

The SAS had never been deployed on home soil before. It’s a slow inexorable build, where the audience discovers itself breathing in time with the SAS team as they are waiting to go in. We know what the result will be but the film still makes us wonder.

During the aftermath, Jamie Bell’s Rusty takes some executive action against one of the terrorists and we gasp at, what seems to innocents like us, to be an execution.

That’s when you know you are getting – putting aside the politics – something honest, insightful and unusual.

The famously reticent SAS have decided that they finally want this legend of their heroism to be released, but maybe they also want us to know what else they did in our name. And ask, who else might share in their complicity?

6 Days is currently playing in the New Zealand International Film Festival and will open commercially in New Zealand on 7 September.