Private prisons are always worse than public ones because they're under constant pressure to cut costs, says investigative journalist Shane Bauer who went undercover in a private US prison as a guard.

Photo: AFP / FILE

New Zealand has an on again off again relationship with the idea of private companies running prisons. Right now, we have the fourth-largest population of inmates in private prisons in the world - more than the United States.

Investigative journalist Shane Bauer took a job as a guard at a private prison in Louisiana in order to peel back the barbed wire and see first hand what goes on inside at least one American private prison.

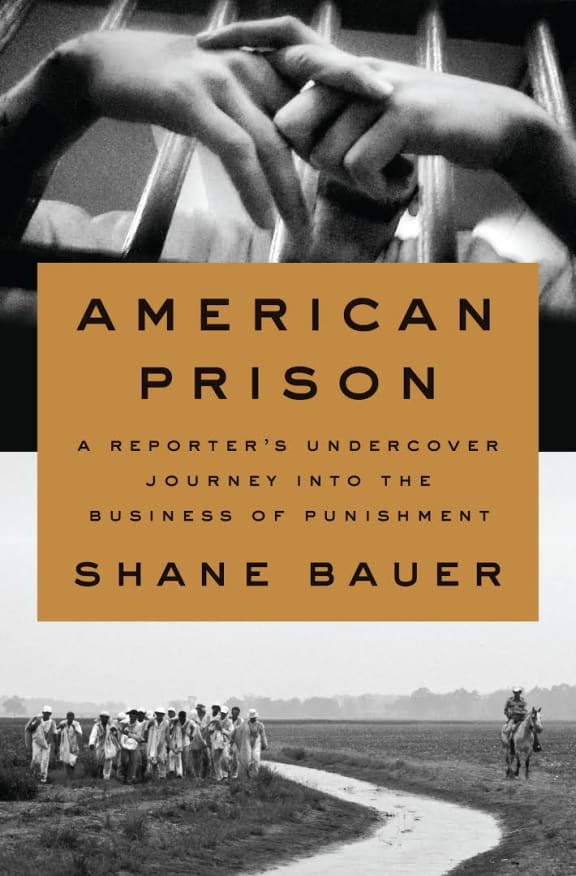

He explains how profit and prison collide in his new book American Prison: A Reporter's Undercover Journey Into the Business of Punishment.

Prisoner in Iran

Before he was a guard however, Bauer was a prisoner - in Iran.

"I had been living in Damascus, Syria at the time, I had been working as a journalist in the Middle East," he says.

Photo: 123rf

He says he and some friends took a holiday to Iraqi Kurdistan, which was considered safe for visitors.

"We were at a local tourist site, a waterfall and we went hiking along a trail near the waterfall, didn't realise how close we were to Iran and we came near the border and were called across by some soldiers.

"They were actually Iranian and they arrested us - and there started a long process where Iran essentially using us as political bargaining chips with the United States and it took us two years to get out.

"It was tough, I was in solitary confinement for four months, generally isolated from the world for the entire two years that I was there - didn't know when we were going to get out."

From locked up to locked out

He says when he did return to the US, he thought he would return to his career reporting in the Middle East, but his unique insight on prisons led him to cover a different story.

"There was a large hunger strike in California - people protesting the use of long-term solitary confinement, this is a hunger strike inside prisons … I ended up doing a long investigation on that."

"I found that we have about 80,000 people in solitary in the US, with people for 10, 20, 30 years - 40 years sometimes - in solitary confinement."

However, he got frustrated with the lack of access and information available to journalists looking to cover prisons - particularly in private prisons.

"Since they're private companies don't have to abide by many of the public access laws that we have, so it's very difficult to get an up-close look … so I had the idea to apply for a job."

Going under cover

He says he didn't think it would work, but started getting calls for job interviews within a couple of weeks.

"The prison was very desperate for employees - their wages were set at a corporate office and they're contending with the fact that they're offering $9 an hour for a very dangerous job, and very few people want to take it.

"The head of training literally said to us 'if you're breathing and you have a driver's licence and you're willing to work, then we're willing to hire you.'

He says although his experience in prison before had been tough, in a way it perhaps made it less scary than for others, but there were some eye-opening revelations about private prison.

"In training they actually told us that part of our job is to deliver value to our shareholders.

"On my second day of training this came up, the instructor asked us what we should do hypothetically if we see two inmates stabbing each other … he says 'your job is to shout at them stop fighting, do not get in between them'.

"He said what's important to us is to go home at the end of the day, and 'if those fools want to cut each other up, then happy cutting'.

'Happy cutting'

He says in some ways, everything at the prison hinged on that same attitude.

"We're supposed to do the bare minimum that is protecting the company from lawsuits: we can say that we intervened if we shout at the prisoners, but we are not putting ourselves in a position where we might get hurt and thus cost the company money.

Photo: Supplied

"The margin of profit that these companies have is not that high, so they're under extreme pressure to cut corners wherever they can."

He says healthcare is one example.

"I met a guy … who had been going to the infirmary for months complaining of pain that was so severe that he couldn't sleep.

"He was asking to go to the hospital and they would just give him [ibuprofen] and send him back."

He says another man kept collapsing because of severe chest pain who they wouldn't take to the hospital.

"What I learned is that their contract with the state required that if the company is to send somebody out to hospital they have to pay for it.

"The state is paying the company $34 a day for each prisoner - a hospital bill in the United States is going to the thousands of dollars, so it's a really significant expense."

Staffing was also affected.

"Staffing is one of the main costs of running a prison so one of the main ways they raise money is lowering wages and keeping low staffing levels in the prison.

"They also cut vocational programmes, rehabilitative programmes. There's guard towers around the prison, they took the guards out of the towers to save money.

"I actually met a prisoner who was up for release and he spent an entire year in the prison after he was eligible for release - because he had been in prison for over 20 years, he didn't have a place to go to.

"It was up to a staff member in the prison to find him a kind of halfway house to go to - and she just wasn't doing it. So he stayed another year, they made however many thousand dollars from his stay.

"The result is a prison that is almost always more violent than its public counterpart, has worse healthcare and worse rehabilitative options."

Constantly on guard

Bauer says he'd gone into the prison with the intention of being an easy-going humane guard - but that was tough to maintain and he quickly felt that being eroded.

"I'm in a place, a unit with over 350 prisoners and there's only one other guard so I'm extremely overextended and that becomes very exhausting.

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

"When I would have to refuse to help certain people, I would start having tension with them and there's just a kind of spiralling where people on both sides of the bars are frustrated.

"The prisoners are frustrated because their classes are getting cut all the time, they're not getting their meals on time, they're not getting to go outside sometimes - because there's not enough staff.

"It just becomes this vicious cycle where they're lashing out at me and I have these personal gripes with them - even though in my mind I know that this system is very problematic still I have to deal with people day in and day out."

He says the experience is probably similar in public prisons, but the pressure of the low staffing levels, low pay and low morale of the guards made things worse.

"We also didn't have any way to protect ourselves, we just had a radio which would not have been the case at a public prison."

Photo: 123rf

"It's not to say that public prisons in the US are beacons and have some kind of ideal of rehabilitation or anything like that - conditions in public prisons are also very bad in this country - but there are ways that the private prisons are worse."

Still, there was a kind of camaraderie between prisoners and guards, he says.

"They would basically bond over their shared disdain for the company … prisoners would always tell us 'you guys, they're not paying you enough, you guys are exploited from this company too' and guards really felt that.

"I remember one day that we were kind of just sitting around talking. One of the cadets said 'I've broken the law before' - she was saying on some level it was a kind of chance that it ended up her on this side of the bars."

Exposing exploitation, and futility in politics

He says a few weeks after he left the prison, they found out he was a reporter and tried to stop any bad publicity.

"The company then threatened to sue Mother Jones which had published an original article that I later kind of developed into the book."

The made their money partly from the individual prisoners - but they also had reputation and shareholders to think about.

"The prison I was in, the government would pay $34 a day - other states, California it's around $80 a day.

"That was the government fee, but the company if course also traded on the New York stock exchange so they had investors - most of which were banks and mutual funds."

Their attempts did not work, though.

"A few weeks after we published I was invited to speak to the department of justice about private prisons and following that the Obama administration announced that they were not going to use private prisons anymore on the federal level.

He says the contract for that prison was abandoned by the company after that, and things were looking better for a while.

He says another private company has also since taken over the prison he had been working at.

"And the state basically cut their fee - to, I think it was $25, $24 a day as opposed to $34 - and the company that now runs it is offering almost no services, it's essentially being run as a jail so people are just being kind of held and fed."

And the initial company is back in the black thanks to President Trump.

"His justice department - very shortly after he was inaugurated - reversed the Obama era decision … they're fully back on track."

President Donald Trump and Melania Trump walking part of the way during the inaugural parade to the White House. Photo: AFP