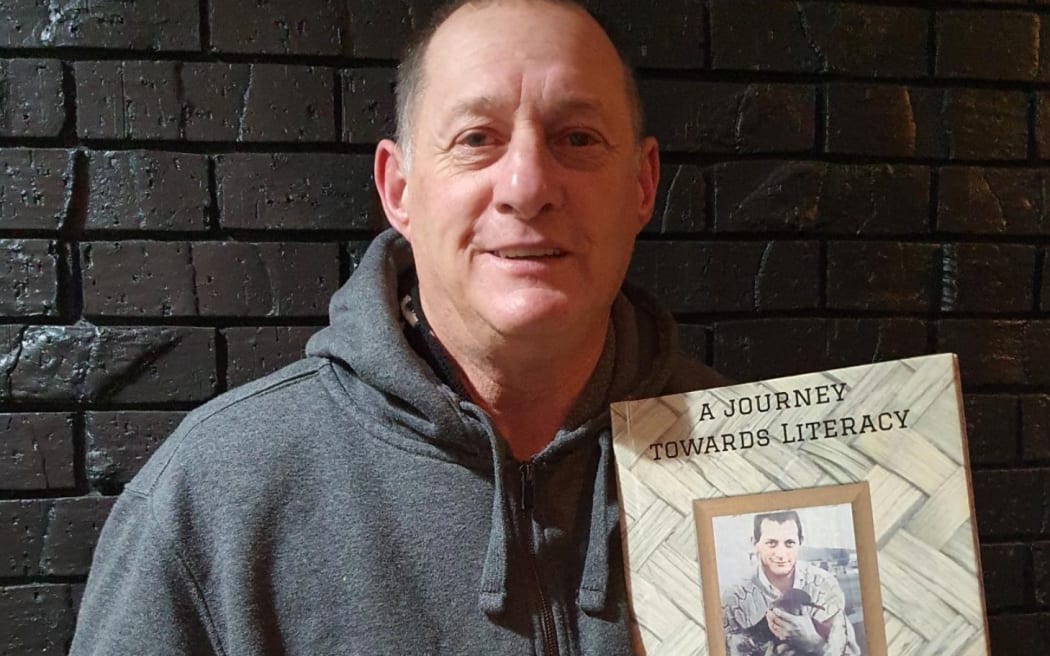

Michael Kingpotiki with his book, A Journey Towards Literacy. Photo: Supplied

Until his late 50s, Invercargill man Michael Kingpotiki would tell a "wee white lie" when he was given something to read, saying he didn't have his glasses handy.

The truth was that the former farm manager didn't know how to read or write.

At the age of 57, with a desire to connect with his grandkids over bedtime stories, Michael reached out for help and connected with volunteer literacy teacher Linda Davies.

Now, three years and countless video chats later, Michael has self-published the short biographical book A Journey Towards Literacy to share his story with future of generations of his family.

Michael tells Kathryn Ryan that as a 12-year-old, he did ask a primary school teacher for help – but was refused.

"I was watching everybody else reading in the classroom and I just wanted to do the same … So I went up to a certain teacher and asked 'Could you teach me to read?' The reply was 'Sorry, it's too late, Michael. You're too old now'.

"It put a dampener on my whole life, really. I just grew up thinking it's not meant to be, so I didn't learn to read."

"[I thought] I'm that dumb, I can't be taught. You just felt I'm not that bright so I can't be a priority to teach. You grow up that way. I went through my whole life thinking like that and feeling that way."

After leaving school at 14, Michael worked in a series of jobs that didn't require reading skills – fisheries, forestry and farm management.

To get his car and motorbike licenses his older brother helped him memorise the road code and any paperwork he'd take home for his family to help with.

As managing farms involves a lot of paperwork, Michael had to get good at memorising information and "survive" at work however he could.

"You told white lies … You worked harder than anybody else because if the boss knew that you couldn't read or write, in your mind they'd say 'sorry, this job is not for you and you can't be here anymore, you're a liability.

"It's always on your mind. So I worked harder than anybody else [thinking] the boss won't get rid of me if I'm an honest worker.

"It's stressful but you have to do it. I had to it."

It was after watching his wife Margaret read a bedtime story to their grandkids one night that Michael finally decided to take the leap and get some help learning to read.

"The kids are looking at my wife like every word mattered to them. And that was the eye opener for me that hey, I want that look in their eyes looking at me. I want to just do the same thing.

"And that's the reason I want to read and I found a lady like Linda to help me."

Linda, a retired primary school teacher, was working as a volunteer literacy coach with the Rural Youth and Adult Literacy Trust.

Micheal says his biggest fear about meeting her was being treated like a child.

"A person of my age getting spoken to like a child, it downgrades you and you probably wouldn't do it.

"I found Linda and she didn't do it to me. Half my fears were done with there and then. That was a big step for me."

In the first four sessions together, Michael and Linda chatted and got to know each other, but soon they were jumping on a Google video chat 4 or 5 days a week.

Today, reading and writing are still a challenge but he enjoys reading online articles and newspapers: "I read my own article last night in the Otago Times. That was amazing."

Confidence in reading aloud kids' stories is an area that he and Linda are still working on.

"I want to make a story sound like a story. And I'm learning, I'm starting to learn that with Linda.

"She's a lady that… If I could send her a medal I would."

Linda says she has never had a literacy student as dedicated as Michael and as a teacher who is "not a very good speller", she also had some understanding of his challenges.

"I had poor self-confidence when it came to writing ... anything on the board I couldn't spell quickly.

"We sort of hit it off because I had something that bothered me and he had something that bothered him. And together, we just worked really well."

Michael was really keen to learn, Linda says, but also had to get through a lot of shame about not being able to read.

"[I said] 'Well, look, I am a school teacher who finds it hard to spell. [There should be no] shame in not being able to read… the shame should be [on] the teacher who didn't have any teacher who doesn't take the time to help a child that wants to read."

Coaching him and watching him achieve has been "magic", she says.

"To have a student that's willing, that will keep trying, that will turn up, that wants to read… I admired his courage to come and say that he couldn't read at that age.

"Most of the students I had could read a bit – Michael couldn't. And I thought what courage and how brave is he to go and do that and to be put with someone he didn't know, and to be put with an old school teacher, too, when school teachers hadn't treated him very well. I was just amazed by the courage that he had.

"Sometimes it was a bit of a struggle but boy, the days when it went well it was just great. You know, you feel so good. It's a very rewarding thing to do, I love it."

For Michael, learning to read as an older adult has been one of the hardest things he's ever done but also one of the best.

"To get the embarrassment out of your mind, the embarrassment that you can't read or write and tell somebody, that is the hardest thing.

"My embarrassment went on to the age of 57. I had to change the way I was doing things and I wanted to do things for my family. The best idea I ever had in my whole life was taking that first step."

He encourages anybody else who wants to learn to read and write to follow his lead and "just take the first step".

"It's your pride holding you back more than anything else. It really is."