An extraordinary prehistoric landscape secret has been revealed in the UK.

New research published in the journal Internet Archaeology outlines the discovery and mapping of a giant circle of buried shafts near Stonehenge.

The pits, which are 9 metres wide and 5 metres deep, are the largest prehistoric structure ever found in Great Britain.

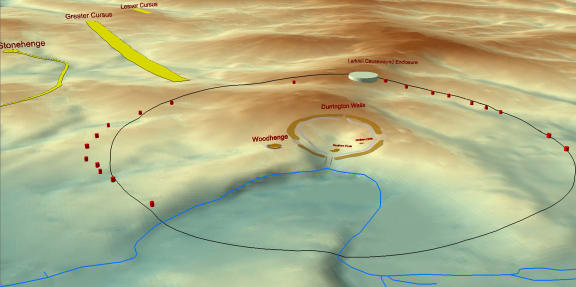

They are located near Durrington Walls, a Neolithic henge two miles from Stonehenge.

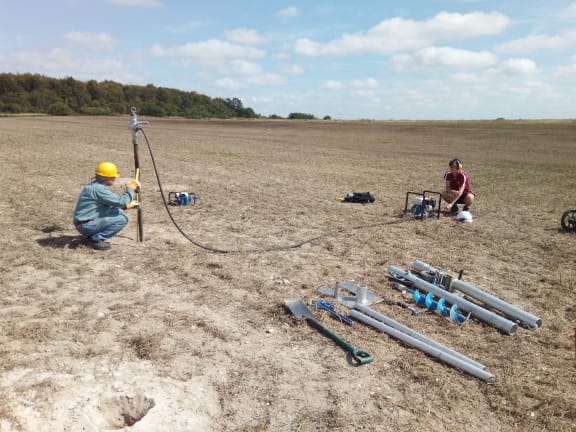

Archaeologists used remote-sensing testing and ground sampling to map the pits which are buried under layers of loose clay.

Professor Vincent Gaffney is Anniversary Chair in Landscape Archaeology at the University of Bradford, part of the Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project and the lead author of the study.

He says this discovery has completely transformed how the landscape is understood.

“We have managed to locate, using geophysical survey, a series of immense pits ten metres across five metres deep forming a massive circle over 2 kms across around the henge of Durrington Walls.

“About 3km from Stonehenge in what most people would have thought was the most studied landscape in Britain, and possibly the world.”

Stonehenge, he says, doesn’t stand alone, it exists in a very complex landscape.

“The Stonehenge landscape is just one immense ritual landscape, but it fits together in ways that we’ve never appreciated before.”

It is unclear exactly what these huge pits are for, he says.

Prof Vincent Gaffney Photo: supplied

“We don’t really know, they are so big, what we’ve had to do with them so far is actually take cores through them to retrieve dating material. But there’s bone, worked stone within them we know that.

“But their practical use, if you can apply the word practical, in these contexts is currently unknown.”

Despite several centuries of archaeological and antiquarian work around the site of Stonehenge most of the landscape is unknown, he says.

“It’s terra incognita and the problem with that is the absence of evidence has become the evidence of absence. The presumption is there’s nothing there.”

Applying geophysics at a “grand scale” at Stonehenge allowed archaeologists to produce maps of land in between the known monuments.

“And the consequence of that is surprise, surprise – it’s full of stuff.

“Some of the stuff we’ve never seen before and the ultimate evidence for that are these pits, because they are so large and yet we haven’t had sight of them.”

The mapping gave a more complete picture of these pits, some of which were already known – explanations for them ranged from theories about them being ancient ponds for animals to natural features.

“We realised we could see nine of them stretching in a massive arc form the river Avon and that arc coincided with a northern arc

“We ended up with 20 of these things in two massive arcs around the henge monument and nature doesn’t produce things like that, they have to be either dug and man-made or alternatively some of them may be natural features that have been appropriated and added to over time.

“Whatever they are, they are critical feature of this landscape and we do need to know more about them.”

The new discovery looks like “a massive cosmological statement”, he says.

“The capacity to lay out a string of massive pits nigh on a kilometre away from the henge monument over valleys and low hills is actually quite interesting.

“Because it’s such a distance and the implication of laying out a circle at that distance seems to be that these people have the capacity to count and tally.

“You wouldn’t be able to memorise the distance of 850-odd metres away, you have to be able to pace it out and count it out.”

Evidence for counting in such an early period gives us a massive insight into these societies, he says.

“The reason they were counting was to help them measure out their cosmology into the landscape and then to dig these huge pits at a specific distance in order to record that cosmology or belief system.”

The scale of the operation suggests some kind of ritual, Gaffney says.

“To a certain extent it’s true that there is no such thing as a ritual site there’s only sites in which rituals occur. But none the less the investment in sites like the henges and both at Durrington and Stonehenge involve mobilisation of large communities for esoteric and probably arcane purposes much of which we don’t entirely understand.”