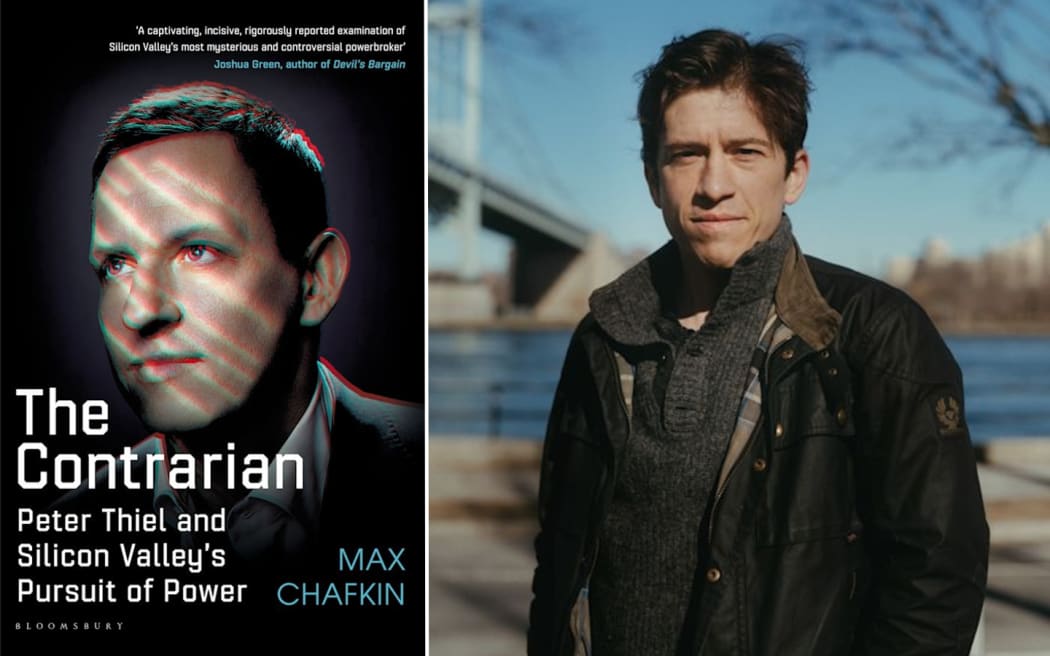

Elusive venture capitalist and entrepreneur Peter Thiel has been thrust under the microscope in a new biography The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley's Pursuit of Power.

Author Max Chafkin, who is a features editor and tech reporter for Businessweek Bloomsburg, spoke to former colleagues, friends, and people who knew Thiel to paint a picture of the notoriously private billionaire, who is a New Zealand citizen and owns a large property on the shores of Lake Wanaka.

In the book, Chafkin aims to pull apart the mythology of Thiel, which he says cuts both ways - the left-leaning media portrays Thiel as a supervillian behind every evil thing that Donald Trump or any tech company has ever done, but that is counterbalanced by a superhero story in tech circles which see Thiel as a great investor, builder and intellectual.

Photo: Supplied

Chafkin says both stories have kernels of truth, but neither gets to the core of Thiel and his motivations.

“I approached this project journalistically and really tried to suspend making judgments. I think that there's a lot to admire in Peter Thiel; he has been a very successful investor, he has been involved with companies that have influenced our lives in profound ways.

“But I think there is another side to him and, and I did try to explore that and maybe explore that in ways that that haven't been done as much in the past.”

Thiel’s political views are a long way off the mainstream, Chafkin says.

“His extreme libertarian views, his support for this kind of ultra nationalist, far-right political faction in the United States.

“But there's another part of it too, which is his belief that tech billionaires should be able to kind of get away with anything, that tech billionaires should effectively rule the world.”

Thiel is a believer in the Silicon Valley ethos of move fast and break things, Chafkin says.

“It's this idea that tech companies should grow as big as they can, as fast as they can. And that the rules, regulations, institutions, all that stuff not only doesn't matter, but are sort of meant to be broken, that there's almost a social good in breaking the rules and sticking it in the eye of society.

“And I think that those ideas, while they were probably very useful to Facebook, especially in its early days, and to many of these tech companies in Silicon Valley, I think they've become much more questionable when those companies are the biggest companies in the world as they are today.”

And he has funded, or is funding, some pretty bizarre projects from ‘seasteading’ — where free, floating cities are created out of the reach of conventional government — to the charter cities movement, says Chafkin.

“It's like seasteading, but on land they're trying to find countries, friendly countries, often in the developing world that will allow them to carve out a free economic zone or something like that.”

Thiel seems to embody many inconsistencies, Chafkin says, his support of Donald Trump being a prime example.

“Peter Thiel himself is an immigrant, he was originally born in Germany, he’s an immigrant who happens to be gay, who happens to be obsessed with the future, who would throw all of his weight behind an anti-immigrant from a political party, the Republican Party in the US that is, in general, pretty hostile to the interest of gays and lesbians, and a candidate who is hostile almost in every way shape or form to technology.”

Chafkin believes when Thiel stepped in to support Trump as his campaign faltered 2016 he was “buying low”.

“Politically, it made a lot of sense for Peter Thiel to try to get on the inside with Trump. His donation to Donald Trump, which happened in mid-October 2016, shortly after the Access Hollywood tape, which, many people thought had tanked Trump's candidacy, Thiel gives him this money.

“And I regard that as he was buying low, basically, he was investing in Trump, he was buying low at the time when Trump seemed to be at his weakest when the rest of the Republican donors and many of the mainstream Republicans were backing away, trying to get as far away from the guy as possible.”

It paid off and one of Thiel’s businesses, Palantir — a military data analytics firm — has subsequently prospered, Chafkin says.

“I mean it's possible they would have done all right, without having connections with the President of the United States.

“But the nature of these big defence procurements, you know, we're talking hundreds of millions of dollars per contract. They are inherently political and Palantir, I think we can say was well positioned politically whether or not they took advantage of it — I suppose it's an open question.”

Thiel’s libertarianism is overstated, Chafkin says, he sees him more as an authoritarian.

“He’s very sceptical of democracy, he has talked about this, and has supported and encouraged this kind of intellectual project, which is really on the rise in the United States, that argues that we should replace democracy essentially, with a tech CEO. Basically dictatorship by tech.

“It's kind of like fascism, almost by a different name.”

In the conservative political circles Thiel frequents people talk about an ‘American Caesar', Chafkin says.

Thiel is motivated by basic needs, Chafkin says.

“He wants money and power, basically.”

And despite Joe Biden’s win over Donald Trump, Thiel retains much political clout, he says.

“Thiel has kind of very brilliantly walked the line between associating himself with Trump and Trumpism without being blamed for kind of the things that Donald Trump is associated with that have gone really poorly.”

He is funding right-wing candidates in senate races such as Blake Masters and J D Vance, Chafkin says.

“He's got the tech companies on one side, and then he's got this Trumpist influence project on the other side. So, I think he actually has, surprisingly, given all of Trump's failings, he actually may have more power today than he did in 2016.”