As a child watching the film Apocalypse Now, writer Viet Thanh Nguyen felt split in two - was he one of the Americans doing the killing or one of the Vietnamese being killed?

"That moment really brought home to me this idea that stories don't only have the power to save us but that stories have the power to destroy us, as well," he tells Susie Ferguson.

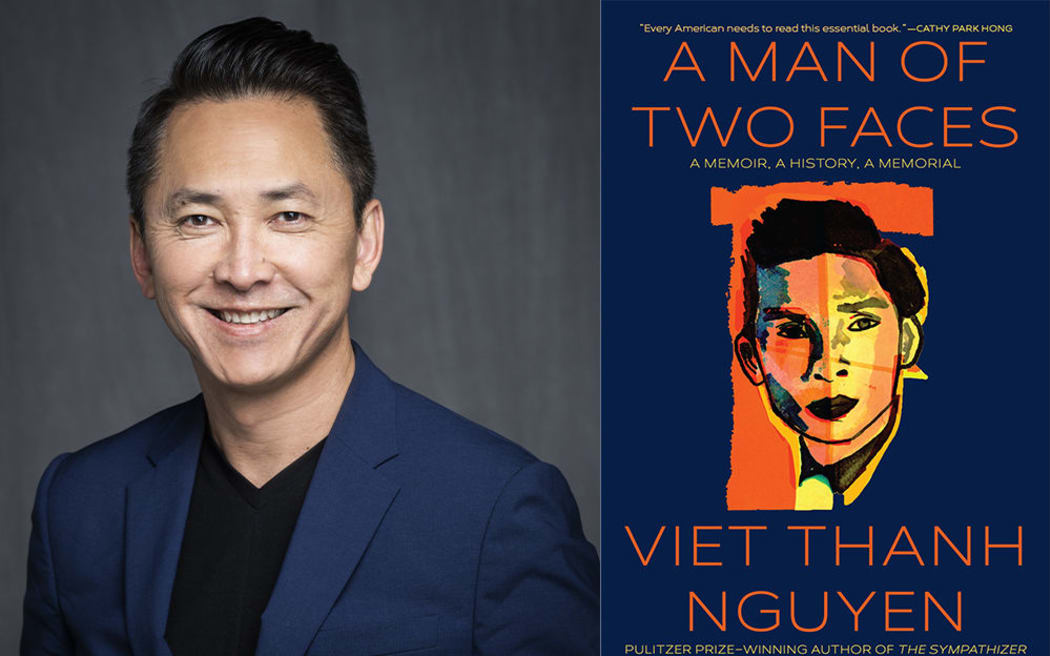

Photo: www.writersfestival.co.nz

Viet Thanh Nguyen's 2016 novel The Sympathizer won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. He will speak about his new memoir A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial at the Auckland Writers Festival in May.

Viet Thanh Nguyen was born in Vietnam in 1971 and his family were among the 130,000 refugees who fled that country for the United States in 1975 at the end of the war.

His earliest memories are of the Pennsylvanian refugee camp they arrived at. With no American sponsor willing to take his family of four, Nguyen was separated from his 10-year-old brother and their parents.

"This is where my memories begin, howling and screaming as I'm taken away from my parents. This was being done for benevolent reasons, to give my parents the time to get on their feet and recover, but when you're a four-year-old child, you really don't understand that."

Nguyen's family had left behind a 16-year-old adopted daughter whose "absent presence" he remembers finding out about at the age of 10.

"The knowledge of my sister's absence haunted me for a very long time but it also imbued me with this sense that I think is very common to refugees and survivors of war, this idea that there is an alternate timeline out there where our lives might have ended up completely different if some circumstance had changed."

At this moment in world history, there are an unprecedented amount of refugees, Nguyen says.

He prefers the term 'phenomenon' to describe the situation of these 100 million displaced people as 'crisis' gives them too much personal responsibility for the situation.

"Refugees are produced by forces beyond their control in terms of war, politics, economic and climate catastrophe. And for those things, we are all responsible but we blame refugees instead."

While being a refugee was very difficult, Nguyen says he's grateful the experience gave him "the requisite emotional damage" necessary to become a writer.

Growing up he didn't recognise this, though, and considered himself "very even-keeled" until his future wife made him aware he'd been numbing himself emotionally.

"My maturation as a human being, as a person, as a father as a husband, but also certainly as a writer, has been tied into my increasing understanding of how much emotional damage was inflicted through the refugee experience, even though I was not an eyewitness. History damaged my parents and therefore damaged me, as well."

As a child escaping the troubling reality of both parents always away working at their shop, Nguyen turned to books.

"I would go to the library every weekend, and come home with a backpack full of books ... I was really escaping to beauty and storytelling - that's what really made me want to become a writer.

"As I delved deeper into my own history and the history of Vietnam in the United States, of course, I realised that my desire for beauty and for storytelling and to become a writer was inextricably tied to this traumatic history, as well."

Watching American movies about the war in Vietnam, as Nguyen did as a child, is an exercise he "recommends to no one, especially if you're Vietnamese or Asian."

"What became very evident to me was that we, Vietnamese and Asians, have no place in the American imagination, except to scream or cry or curse or beg to be rescued."

At a college screening of Apocalypse Now, he was able to articulate to his class how these films affected him.

"I remember shaking with rage and anger as I recounted the scene in the movie where American soldiers massacred Vietnamese civilians. Up until that point, I was an American rooting for American soldiers, having watched a lot of American war movies.

"At that point, however, watching these Vietnamese people being murdered, I was split in two - not sure whether I was the American doing the killing or the Vietnamese being killed.

"That moment really brought home to me this idea that stories don't only have the power to save us but that stories have the power to destroy us, as well."

As the "unofficial Ministry of Propaganda" for the United States, Nguyen says, Hollywood productions have an enormous cultural reach.

And although you'd imagine movies like Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket and Platoon would make people very critical of Americans' conduct, because they're the ones telling the stories it's with them that viewers empathise.

"In these movies where Americans are committing atrocities, they're still the centre of attention and even though the Vietnamese people are the victims, they are completely silenced, as well ... So, ironically enough, the world knows the Vietnam War via American perspectives, and continues to feel for Americans and see through their point of view. "

Like most people, Nguyen says he craved a sense of "belonging" growing up that as a refugee wasn't available to him.

Later, experiencing racism and categorisation as 'other' made him distrust this desire to be "on the inside".

"In order for us to feel utterly safe and comfortable it is all too human of a response to then demonise someone on the outside and to put our fears and our desires onto that other."

Americans categorised as 'other' are given "a very problematic opportunity" to talk about their particular trauma - in his case the Vietnam War - but not really about anything else, Nguyen says.

In his writing, he draws a direct line between the Vietnam War, American history and current divisions in the United States.

"I connect the failures of the war in Vietnam to the original contradiction that the United States is built upon, which is that we are a country of freedom and democracy - that is true for some people - and we're also a country that has been built on genocide, colonisation, slavery and warfare."

Most countries are built on moments of terrible violence that stand in "enduring contradiction" to their national mythology, Nguyen says.

"There's always something shameful and terrible we have done as a nation that has contradicted our mythologies. In that, there's tragedy and there's also comedy in that absurdity and hypocrisy. "

A Catholic childhood - "I like masochism, suffering, sacrifice and martyrdom and all that" - and "pure ignorance" are what Nguyen says got him through the miserable 17 years he spent writing the 2017 short story collection The Refugees.

The long haul taught him endurance, which he says is a key skill for a writer.

"You have to find it within to just persist, no matter what anybody else thinks positively or negatively about your writing."

In that process, Nguyen also discovered his creative 'voice', which he defines as "an expression of one's authenticity, what one truly believes".

"I don't think you know what your 'voice' is when you start off being a writer. It takes all that discipline and effort and sacrifice to both discover the art and to discover the voice."