A petition can be an effective way for the public to get the attention of Parliament, and it doesn’t necessarily need lots of signatures.

It’s not often that a petition to Parliament results in a law change, but changes can occur as a result of MPs considering a petition and digesting submissions on the topic. It’s a journey that the petitioner invites MPs and the wider community to join them on, and sometimes it can venture quite far into the territory of Parliamentary process.

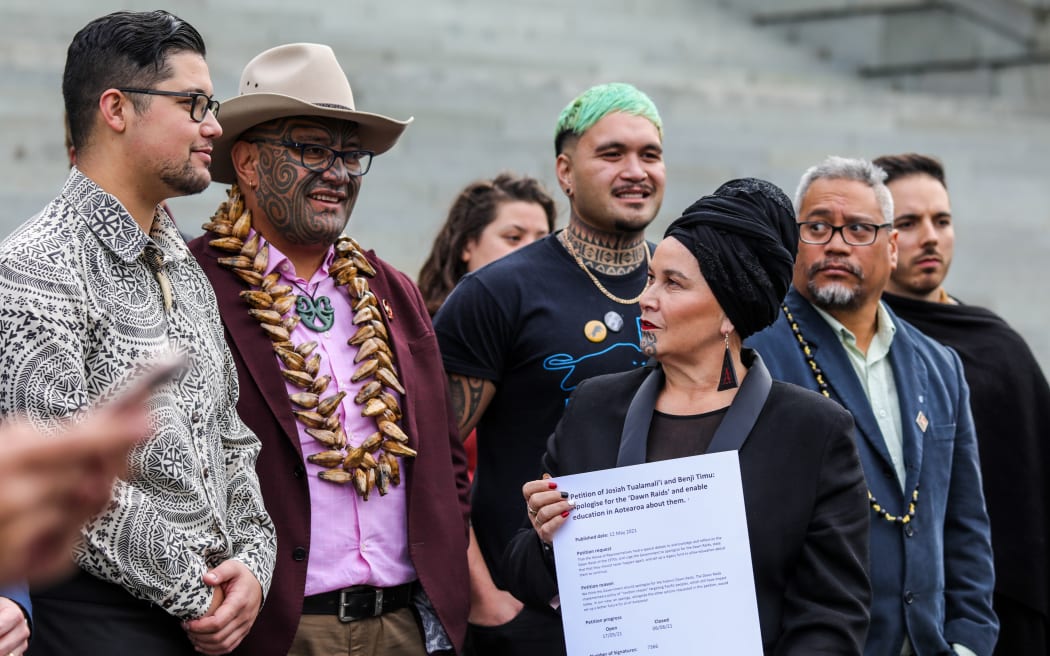

Te Pāti Māori co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer alongside other MPs holds the Dawn Raids petition after co-petitioners Josiah Tualamali’i (left) and Benji Timu (behind her) presented it on the steps of Parliament, 21 June 2021. Photo: RNZ / Daniela Maoate-Cox

When it was first established as a specialist committee in the last Parliament, the Petitions Committee considered about 430 petitions in that 53rd Parliament. About half of these resulted in a basic report to Parliament by the committee; roughly a quarter were referred to other committees; and about 20 were referred to a government minister for response. Regarding previous Parliaments, in the 52nd Parliament, 240 petitions were reported back by select committees; in the 51st, 144; and in the 50th, 114.

A select few petitions have resulted in a Special Debate by Parliament. The relatively new provision of Special Debates offers MPs the opportunity to speak about other issues that aren’t immediately about legislation, relating for instance to some of the areas that committees have been working on and reported back to the House about, things that otherwise wouldn’t be debated.

Mobility Parking

Last month a Special Debate was held on a petition that had been presented two years earlier, requesting that Parliament change the law to substantially increase fines for misuse of mobility parking spaces, including on privately-owned land that is used publicly, and urging the government to run an education campaign to desist able-bodied people from misusing mobility parking spaces for public use.

The petitioner, Claire Dale, faced numerous hurdles in getting traction with her petition, from launching on the day of a Covid-19 lockdown, to pandemic disruptions, to trying to present the petition when Parliament grounds were occupied by anti-vaccine mandate protestors. In the end the petition had a few thousand signatures.

Advancing the petition was a steep learning curve, she says, and involved invaluable support from NGOs to publish her press releases and from staff in Parliament’s Office of the Clerk who nudged her in the right direction in terms of process.

Claire Dale presented a petition to Parliament seeking to make mobility parking enforceable on all public-use property and increase fines. Photo: Supplied

When the Petitions Committee’s recommendation for a Special Debate on the petition came just before the House rose for last year’s election, Dale didn’t initially like her chances of it going ahead. But it did, in the new Parliament term. The effect of the petition, in raising awareness about the plight of people affected by mobility parking shortfalls, had been well absorbed by the 12 MPs who spoke.

“People in Parliament lead very busy lives that are structured and happen in very specific ways,” Claire Dale says, “and while MPs for different areas may have an inkling of what the needs of their community are, I don’t think it’s until a petition is put together and people respond to it that they really understand how important those things can be.”

After her petition served to remind MPs that New Zealand still needs to comply with the UN Charter on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which will require action is taken in this area, Dale says she’s confident that legislation will happen. “My only question and my only concern over this is how long it will take.”

Dawn Raids

Another example of a petition that made a significant impact was lodged in the 53rd Parliament calling for an apology by government for the racist policies and actions of the Dawn Raids of the 1970s which targeted Pasifika communities, as well as calling for a legacy fund so the raids can be taught in schools, and for a Special Debate in Parliament about the issue.

The petition, which received 7366 signatures, was organised by Benji Timu and Josiah Tualamali'i, the latter of whom says they launched it as a way of acting on community expression.

“I guess we just felt it was the right thing to do and because it was a cross-generational thing. Elders had gone out there and made this call for an apology and the government had asked them their opinion and we just felt that we should, as younger Pacific people, speak in support,” Tualamali'i explains.

Bringing the petition to Parliament, where it was received by MPs from various parties, and hearing the Special Debate on the Dawn Raids, when emotional speeches from across the House were heard, felt momentous. Tualamali'i says it gave a sense of the wider support for their petition.

MPs, supporters and the co-authors of the petition gather for photos. Photo: RNZ / Sean Aickin

“[Petitions are] another vehicle we can use, and maybe we might not always get a Special Debate, but one good thing I've found in other petitions I’ve taken is that the committee does write back to us and sometimes asks to see us. Generally they want to know what will help. They’ve always been open to hear, which is a really good thing about our democracy.

“Government and parliament are different, and sometimes government might not feel like the natural home for us to talk to, and we don't have to talk to government alone. You can talk to the Parliament and that’s not party-dependent which is another nice thing for some of us, where you can talk to all of them at once. A petition is a great vehicle that's apolitical.”

Tualamali'i says he thinks about elders and others who in the past had to take petitions around the community, door to door, in order to get people to write their names down in support, whereas now it’s usually organised online which is generally more accessible for people.

Numbers

“One good thing about the petitions I've learned from this is that it only needs one signature and they will consider it, so… it's not necessarily the number of signatures that matters,” says Tualamali’i.

“But it's a good way to take an opportunity to have something that’s important to you and have it heard. I'd like more people to know about it.”

Sometimes a large number of signatures makes a petition hard to ignore. For instance, a Private Bill in 2022 which sought to address an anomaly in surrogacy law whereby a mother’s name wasn’t on her daughter’s birth certificate, emerged after a petition signed by 50,000.

However, lots of signatures don’t always get a petition over the line, at least not immediately. A petition in 2003 which carried over 90,000 signatures called for the repeal of 1982’s Citizenship (Western Samoa) Act, which denied New Zealand citizenship to Western Samoans despite a Privy Council finding that they were entitled to New Zealand citizenship. No action was taken by the Government in 2003, but a Member’s Bill currently on the order paper now seeks to restore that citizenship.

So petitions can find different avenues towards achieving change. Even if no law is changed, the attempt in itself can be instructive and help create change indirectly.