“Sharks are very sensitive to electricity. They have a special electric sense and can feel about a billionth of a volt per centimetre in seawater. To imagine what that’s like, if you take a mouthful of saltwater and gargle, that creates an electrical field in your mouth that a shark could perceive from maybe 20 centimetres away.”

Sunkita Howard, PhD student, University of Otago’s Zoology Department

Sunkita Howard and her spiny dogfish study

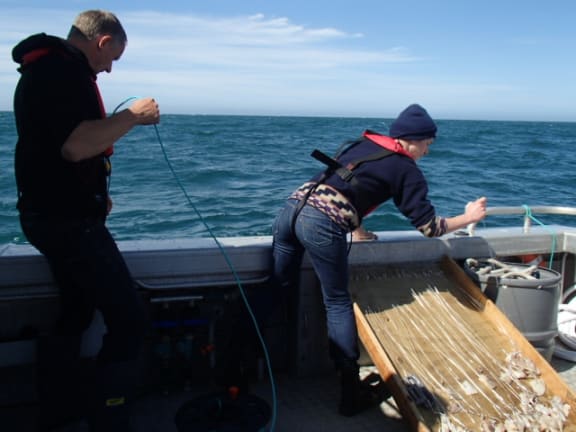

Sharks use their special electrical sense to find food, but PhD student Sunkita Howard is hoping to turn it against them, to help prevent thousands of spiny dogfish getting accidentally caught on baited fishing hooks used in the ling bottom longline fishery.

“Spiny dogfish are not the sharkiest looking of sharks … they’re named after the little spike that’s in front of each of their dorsal fins.” University of Otago PhD student Sunkita Howard.

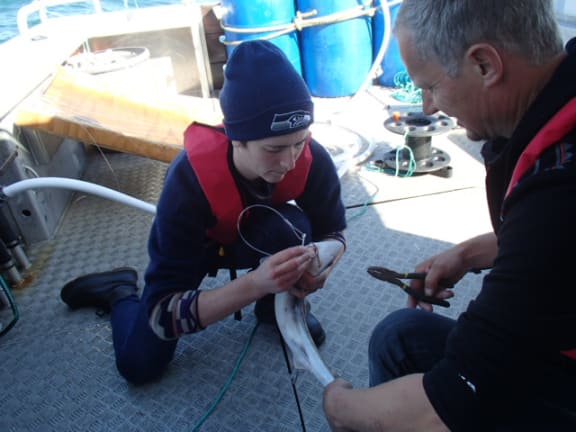

Sunkita Howard unhooks a spiny dogfish from an unbarbed circle hook, used to minimise damage to the shark's mouth. The dogfish will be held in captivity for a few days and then returned to the sea. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

The idea is that a fishing hook emitting a small electrical field will deter sharks but not scare away the bony fish that are being targeted, which lack the shark’s electrical sense.

“When commercial fishers go out setting these great long lines with many, many hooks, targeting ling, they might catch more dogfish than they do ling. It’s not unusual on a really bad day to go out and catch a thousand dogfish on a thousand hooks.”

Using electricity as a deterrent is not a new idea – fishers already use electropositive metal to create a small electric field. A small ingot is attached to each fishing hook, but the metal only lasts a day or two and comes from a factory with a poor environmental record. Sunkita’s aim is to develop a more sophisticated longer-lasting system.

“I use electrodes that are hooked up to a microprocessor and a power supply.” By precisely controlling the electric field used, it might be possible to develop a shark deterrent that is effective and practical enough for use in commercial fisheries.

“What’s really cool is that it is an applied use of what has been for 50 or so years, very much pure blue skies research.”

A spiny dogfish swims around in an experimental pool. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Sunkita says the key will be to develop a cost-effective, re-useable tool that can fitted to every hook on a longline.

Sunkita has been working with Otago Innovation with a view to commercialising the technology. Now that she has successfully conducted tank trials with both spiny dogfish in New Zealand and sandbar sharks in the United States, the next stage would be to conduct field trials.

Sunkita has a strong interest in art, and has been creating art works alongside her experimental work.

She has also been working with an economist to quantify the cost to the fishing industry of shark bycatch.