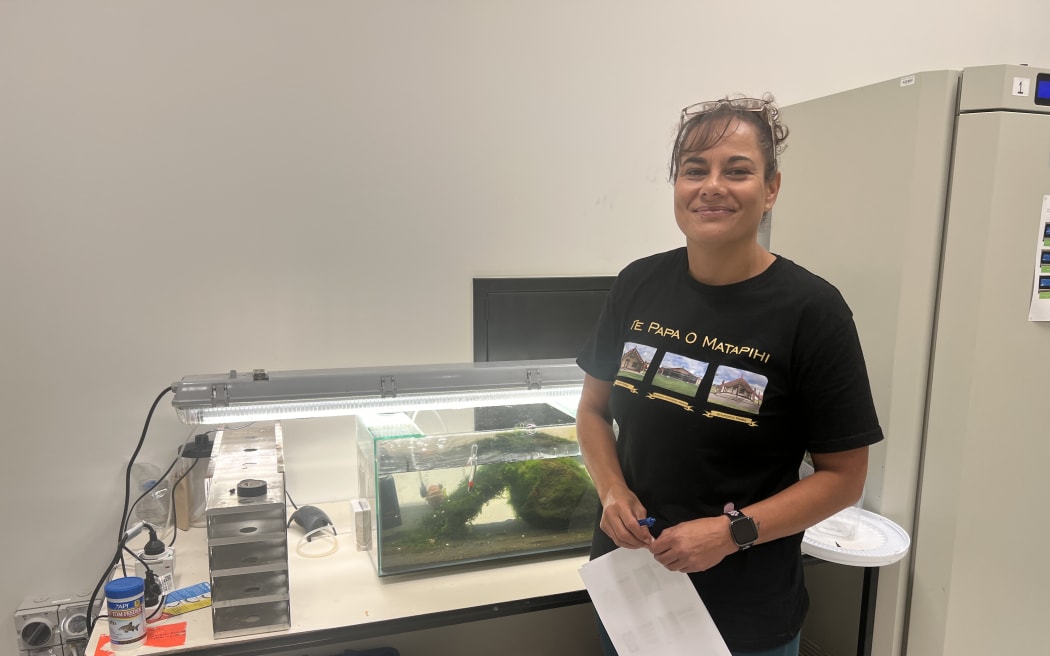

Inside the lab space at the Coastal Marine Field station Kiamaia Ellis checks in on the pēpi kōura, one is not much more than two centimetres in length.

Photo: Justine Murray

Follow Our Changing World on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, iHeartRADIO, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

In another tank one is darker in shell colour and the other is more translucent, Ellis says it’s because of how much light the kōura expose themselves to while in their tanks.

The resilience of pepi koura is part of Kiamaia's research objectives. Photo: Justine Murray

One pēpi is shy and only comes out when it’s feeding time, the observation notes refer to it as the ‘pipe cray’.

“I’m actually quite attached to the pēpi kōura…they’re such characters there’s one there that comes out and dances around and plays and we have a little kōrero” Ellis says.

Ellis’ Phd research project ‘Pēpi Kōura: A transdisciplinary mātauranga Māori and science approach to enhancement and resilience of puerulus kōura in a changing climate” stems from the aspirations of local tangata whenua who according to Ellis have ‘observed the degradation of tāonga species over many generations’. Local iwi put this down to urban, industrial and harvesting pressures.

Te Kehu Butler has witnessed first-hand the impact commercial fishing has had at Mōtiti Island located sixteen kilometres north east of Tauranga. According to Butler the once abundant crayfish pataka kai (food resource) areas have all but disappeared. Butler is a seafood diver and argues that commercial fishing was another problem.

“Commercial fishermen would get a license and they would bombard the whole island…and they’d take all the crayfish it made It harder for us to feed the manuhiri at the marae at different occasions…so when they bombed the island like that the old people used to have to go out deeper to dive for crayfish” he says.

Enoka Rolleston, Te Kehukehu Butler and Justine Murray at Matakana Island. Photo: Justine Murray

In 2013 Ellis spent some time interviewing her Kaumatua to understand the stories and customary knowledge about pataka kai. She’s also drawing on the maramataka (Māori lunar calendar) to correlate the times of recruiting kōura from the harbour.

To determine their adaptability to a changing ocean environment Ellis will on-grow pēpi kōura while assessing how they adapt to different diets and different pH conditions. Scanning electron microscope analysis will help her determine if the crayfish are able to properly develop their important protective shells under the lower pH conditions expected in our future oceans. She will also monitor the mauri (vitality, life essence) of the pēpi while in their habitat.

Ultimately what Kiamaia wants to do is to determine if the pēpi can be safely nurtured to mature adults in captivity, to safeguard this taonga against their uncertain future.

The research project is developed in partnership with the Tauranga Moana Iwi Customary Fisheries Trust, The Port of Tauranga and the University of Waikato and is funded by the Deep South National Science Challenge.