The mooring cable laid out on the ice shows the depth to the sea floor. Photo: Anthony Powell / Antarctica NZ

Follow Our Changing World on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, iHeartRADIO, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic or wherever you listen to your podcasts

Antarctica is losing ice at an accelerating rate, particularly in some parts of West Antarctica.

How did the small and more vulnerable West Antarctic Ice Sheet behave during past periods of natural warming? Geological evidence is sparse, but an ambitious sediment-drilling project aims to change that.

Drilling back in time to explore past periods of warming

SWAIS2C – short for Sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to 2°C – is an international collaboration, co-led by Aotearoa New Zealand. During its first season this summer, the team set up camp close to the grounding line of the Ross Ice Shelf, where the world’s largest slab of floating ice is at its thickest. Below more than 580 metres of ice, only about 50 metres of ocean separate the bottom of the ice from the ocean floor.

The team used hot water to thaw a hole through the ice to reach the seafloor where layers of mud and rock have been accumulating for millennia, building up one of Earth’s memory banks of environmental conditions at the time they were deposited.

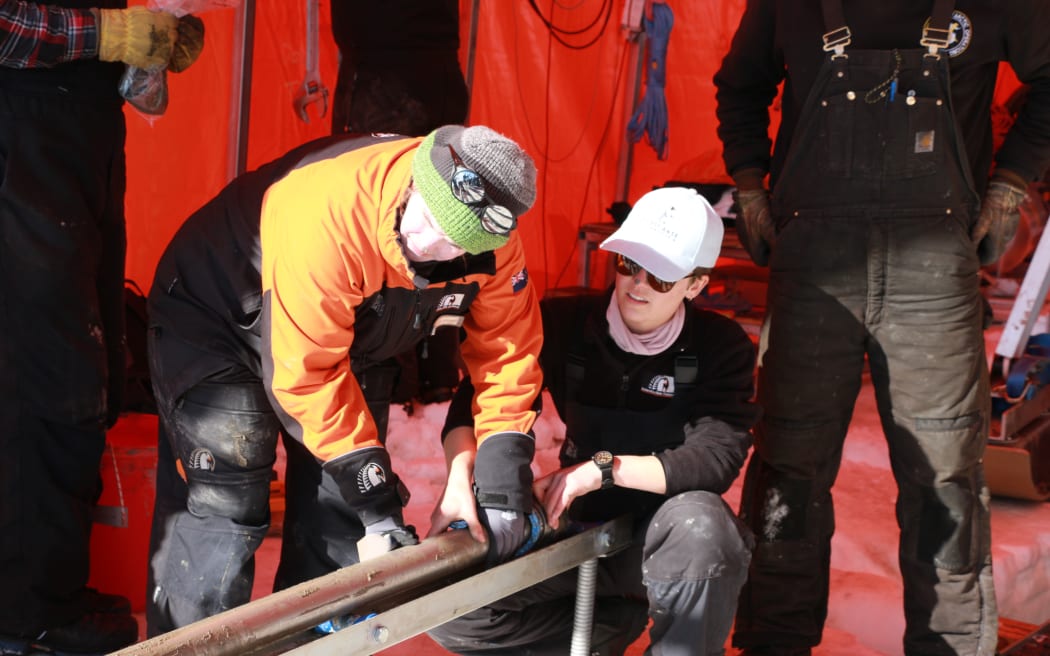

The coring team. Photo: Anthony Powell / Antarctica NZ

Saving the world’s largest ice shelf

The SWAIS2C team successfully retrieved the longest sediment core ever extracted from the remote Siple Coast, which holds clues about the ice sheet’s more recent past. Next season, the team hopes to drill deeper and further back in time to the last interglacial period, some 125,000 years ago, when Earth was around 1.5°C warmer than pre-industrial temperatures – similar to the warming we are approaching now.

Dr Richard Levy hammer coring. Photo: Anthony Powell

The goal is to track whether the grounding line of the Ross Ice Shelf retreated or advanced during this and even earlier periods of natural warming, and what that tells us about the risk of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet breaking up partly, or even completely, in the future.

If the floating Ross Ice Shelf were to melt, it would have no impact on sea levels. But the ice shelf acts as a buttress, holding the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in place. If the shelf goes, the ice sheet would likely follow – and the consequence could be 3–5 metres of sea level rise.

The team retrieved sediment from the ocean floor under more than 580 metres of ice. Photo: Veronika Meduna

Learn more:

- Find out more about the SWAIS2C project.

- The collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is not inevitable – yet.

- An explainer of the difference in climate impacts at 1.5°C or 2°C of warming.

- Listen to more Antarctica episodes from Our Changing World: the physics of ice sheets and neutrino detection, and secrets of Antarctic microbes.

- Listen to Alison Ballance's Voices from Antarctica series.